When the Deepwater Horizon suffered a blowout, caught fire and sank in the Gulf of Mexico last April, it was only forty miles off the coast of Louisiana. Yet, in many respects, the world aboard the ill-fated rig was as alien to most of us as if it had been dropped from outer space. Even within the shipping industry, deep-water offshore drilling is often poorly understood, a world wholly unto itself.

When the Deepwater Horizon suffered a blowout, caught fire and sank in the Gulf of Mexico last April, it was only forty miles off the coast of Louisiana. Yet, in many respects, the world aboard the ill-fated rig was as alien to most of us as if it had been dropped from outer space. Even within the shipping industry, deep-water offshore drilling is often poorly understood, a world wholly unto itself.

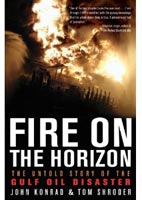

Nevertheless, the catastrophe on the Deepwater Horizon touched us all. The explosion and fire killed eleven, injured seventeen and resulted in the worst accidental marine oil spill in history. The impact, on both the environment of the Gulf of Mexico and on offshore oil policy, is likely to be far reaching. This is why John Konrad’s and Tom Schorder’s new book, Fire on the Horizon: The Untold Story of the Gulf Oil Disaster, is so timely and so welcome.

Konrad knows of what he writes. He is a veteran drill rig captain and a former employee of Transocean, the company that owned the Deepwater Horizon. He also is the founder of the excellent maritime industry blog, gCaptain.com. Konrad is assisted by Tom Schoder, who was the editor of the Washington Post Magazine when the magazine won, not one, but two Pulitzer Prizes.

The Deepwater Horizon was one of the most powerful industrial machines ever built. A semi-submersible, dynamically-positioned, ultra-deepwater rig – it was part ship and part drilling platform. The rig was 367’ long and 256’ wide and was 395’ tall from the thrusters to the top of the derrick, roughly as tall as a 40 story office tower. When she was built in 2000 in Korea, she was the state of the art in deep water drilling. Her eight thrusters could move her along at a stately four knots, but their main job was to hold her as still as possible over the drill site. The ship was almost constantly underway, with her propellers turning, going absolutely nowhere.

Konrad follows the officers and crew of the Deepwater Horizon from her construction at the Hyundai shipyard in Ulsan, Korea, on her delivery voyage around the Cape of Good Hope to the Gulf of Mexico, and on to her final destruction. As an exploratory drill rig, the Deepwater Horizon’s career was successful up until the end. Among other accomplishments, the rig set a record for the deepest offshore well ever drilled, at over 35,000 feet deep.

The story of the Deepwater Horizon takes a drastic change when it is ordered to drill in Block 252, which has been named Macondo. Another rig had already attempted to drill there, but hit an unexpected pocket of natural gas, which almost resulted in a blow out. As repairs to that rig’s Blow Out Protector (BOP) would take time, the Deepwater Horizon was moved to Macondo, to drill what would become known as the “well from hell.”

Despite problems and delays, the drilling at Macondo was considered successful. Only as the well was being shut down, literally cemented closed, so that a production rig could later reopen it, did a blow out occur with disastrous results.

What is wonderful about Fire on the Horizon is that Konrad and Schoder give us a understanding of the conditions aboard the rig prior to the catastrophic blow-out. They put into context the scattered bits and pieces of information that have been reported by the press so the reader can grasp a more coherent whole.

On one hand, Transocean, the rig owner, was obsessive about safety, focusing on avoiding accidents and worker injuries, from slips and falls to dropping tools. In retrospect, it seems a tragic case of not seeing the forest for the trees, or in this case, perhaps the leaves and branches. There is a tragic-comic element when Transocean executives fly out to the rig with officials from BP to celebrate the rig’s seven year record of no-lost-time injuries – just as the rig is about to disintegrate into a flaming inferno.

On the other hand, there were problems on the Deepwater Horizon. The rig needed maintenance. It had not been drydocked in the ten yeas since it had sailed from the shipyard. Its critical Blow Out Protector, which failed so tragically, was five years overdue for its five year inspection. Overall, however, the picture painted of those aboard the rig were of a closely knit team of professionals doing their jobs as well as they could with the tools at hand. Ultimately, Konrad suggests that it was probably a series of decisions made ashore, in the corporate offices in Houston, resulting in shortcuts in sealing the well, that may have the greatest factor in triggering the blowout that doomed the rig.

Fire on the Horizon is a fascinating, sprawling, gripping and disturbing book – a view into a world few outside the offshore industry are likely to ever see. It is a complex and timely story well told. Highly recommended.

This was coming as sure as day follows night and if by chance they get away with this unprecedented travesty...it will be even more apparent we have totally capitulated to the forces that will stop at nothing to destroy the world as we have known it. It is profitable and risk free.

Pingback: First Permit to Restart Deep Water Drilling : Old Salt Blog – a virtual port of call for all those who love the sea

Pingback: Safety – the Forest or the Trees on the Deepwater Horizon? : Old Salt Blog – a virtual port of call for all those who love the sea