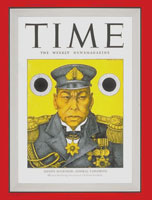

We seem to need to put a face to our enemies. On the cover of Time Magazine of December 22, 1941, the face of the enemy was Admiral Yamamoto, labeled as “Japan’s Aggressor.” The image of the admiral is a scowling caricature in yellow, looking off to one side, personifying an image of Oriental duplicity and betrayal. In the decades following the war, historians have been far more charitable to Isoroku Yamamoto, casting him as a reluctant warrior who understood and predicted Japan’s defeat even while personally planning the attack on Pear Harbor. Ian Toll’s A Reluctant Enemy in today’s New York Times makes this case. I wonder whether this assessment of Yamamoto is not, at times, almost as a much a caricature as the Time magazine cover of 1941.

We seem to need to put a face to our enemies. On the cover of Time Magazine of December 22, 1941, the face of the enemy was Admiral Yamamoto, labeled as “Japan’s Aggressor.” The image of the admiral is a scowling caricature in yellow, looking off to one side, personifying an image of Oriental duplicity and betrayal. In the decades following the war, historians have been far more charitable to Isoroku Yamamoto, casting him as a reluctant warrior who understood and predicted Japan’s defeat even while personally planning the attack on Pear Harbor. Ian Toll’s A Reluctant Enemy in today’s New York Times makes this case. I wonder whether this assessment of Yamamoto is not, at times, almost as a much a caricature as the Time magazine cover of 1941.

Perhaps that suggestion is unfair to Ian Toll, who is a fine historian. His essay in today’s New York Times does make a key point which is too often ignored. Toll writes ” Pearl Harbor aside, Yamamoto was not a great admiral. His strategic blunders were numerous and egregious, and were criticized even by his own subordinate officers.”

The attack at Pearl Harbor was the only the first part of Yamamoto’s strategy. The second part was to defeat the remaining American fleet in a “decisive battle” to further cripple American naval power and force a capitulation in the Pacific. Here Yamamoto failed completely. The “decisive battle” was intended to be what we now call the Battle of Midway, an American victory. Yamamoto’s attempt to strike back with his remaining forces were then stymied by the American invasion of Guadalcanal. As Toll writes “Yamamoto was also directly responsible for Japan’s cataclysmic defeat at the Battle of Midway, and for the costly failure of his four-month campaign to recapture the island of Guadalcanal.”

Fortunately for the Americans, Yamamoto turned out to be a better politician and bureaucrat than admiral. Ironically one of Yamamoto’s innovations before the war was the development of long range land-based naval aviation, particularly the Mitsubishi G3M and G4M medium bombers. These planes had a longer range than their fighter escorts and were lightly constructed. With full loads of fuel they were vulnerable to enemy fire which led Allied fighter pilots to nickname the G4M “the Flying Cigarette Lighter.” Yamamoto would eventually die in one of these aircraft. On April 18th, 1943, Yamamoto was traveling in a G4M fast transport plane when it was ambushed by American P-38 Lightning fighters and shot down.

Much is made of Yamamoto’s prediction that Japan lacked the resources to defeat the United States in a protracted war. Nevertheless, this is not to say that he completely opposed going to war with the United States. Yamamoto did indeed threaten to resign just prior to the start of the war, but it was not over his opposition to the war itself. He threatened to resign if he was not allowed to go forward with his attack on Pearl Harbor. While in many respects, Yamamoto was a “reluctant enemy,” perhaps, he was not quite reluctant enough. Whatever his degrees of reluctance, he also, fortunately, wasn’t a particularly good admiral.

Yamamoto wasn.t that bad of an admiral. He expected at least 1 carrier at Pearl Harbor and moved a huge fleet across the Pacific in secret.

His plan for Midway was masterful but our breaking of the Japanese Navy code tipped us off to the trap and our fleets were already north of Midway when Yamamoto hoped to catch us coming out of Pearl Harbor.

It was also codebreakers that tipped us off Yamamoto was taking that flight and we sent planes to shoot him down.

By missing our carriers twice, he knew Japan had truly “awakened a sleeping giant.”

The codebreakers deserve a lot of credit but if Yamamoto hadn’t screwed up the deployment of his forces at Midway the codebreaking would not have made much of a difference. He sent out his submarine pickets late, then steamed his carriers right past them. He failed to launch a planned aerial surveillance of Pearl Harbor, so he sailed into battle effectively blind. The Americans used the intelligence they had to great effect while Yamamoto did not use the tools available to him. The codebreakers gave the Americans an advantage but if Yamamoto had followed his own battle plan it may not have been insurmountable. He had another opportunity to cripple the American fleet in the Solomons but lost his chance when he failed to retake Guadalcanal. The naval losses at Guadalcanal put the IJN on the defensive for the rest of the war.

As an aside, the “sleeping giant” quote is apparently apocryphal. Yamamoto never said it and the diary entry where he supposed to have used the phrase has never been found.

What I am really objecting to is the simplistic notion of Yamamoto as the master tactician who foresaw inevitable defeat but continued on out of duty. I think the story is a bit more complex than that. If Yamamoto had been a better admiral the outcome of the ar might have been rather different, not necessarily Japanese victory but something less than total defeat.

All that being said I am no historian, so I may have it all wrong.