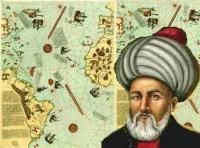

In 1929, a portion of a world map was discovered in the archives at the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. The map showed Europe, parts of Africa and Columbus’ discoveries in the New World. It was drawn in 1513 only 21 years after the voyages of Columbus, by Piri Reis, an Ottoman admiral and cartographer. Last Thursday, a reception was held to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Piri Reis map at the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) Headquarters in London. A new 59 tile reproduction of the famous map was installed on a wall at IMO Headquarters to commemorate the anniversary.

In 1929, a portion of a world map was discovered in the archives at the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. The map showed Europe, parts of Africa and Columbus’ discoveries in the New World. It was drawn in 1513 only 21 years after the voyages of Columbus, by Piri Reis, an Ottoman admiral and cartographer. Last Thursday, a reception was held to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Piri Reis map at the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) Headquarters in London. A new 59 tile reproduction of the famous map was installed on a wall at IMO Headquarters to commemorate the anniversary.

The map is not only an important historical artifact but has also been the subject of speculation involving lost civilizations and even space aliens.

Piri Reis was the nephew of Kemal Reis, an Ottoman admiral who commanded the victorious Ottoman Navy at the First and Second Battles of Lepanto. Reis, meaning “chief,” can be translated as “captain” or “admiral.” Piri sailed with his uncle at the Battles of Lepanto and other Ottoman naval campaigns against Spain, the Republic of Genoa and the Republic of Venice.

The map of 1513 was based on some 20 older maps and charts which Piri Reis had collected, including at least one with information provided by Christopher Columbus. Piri’s uncle Kemal Reis apparently obtained the Columbus chart in 1501 after capturing seven Spanish ships off the coast of Valencia in Spain with several of Columbus’ crewmen on board.

From MuslimHeritage.com: The most striking characteristic of this map drawn is the level of accuracy in the positioning of the continents (particularly the relationship between Africa and South America) which was unparalleled for its time. … Piri Reis’ map is centered in the Sahara at the latitude of the Tropic of Cancer. The surviving fragment of the first world map of Piri Reis drawn in 1513 is the oldest known map which includes the continent of America. The map shows part of Europe and the west coast of Africa, eastern, central and south America, the Atlantic islands, and the ocean. A great deal of detail is given of South America.

The format of the map is that of a portolan chart, a common form at this time. Instead of latitude and longitude grids, compass roses were placed at key points with azimuths radiating from them. The east-west lines through the small rose off South America in the center of the map are a very good approximation to the Equator, both there and with respect to Africa. The small one at the very top of the map is a very good estimation of 45 north where the east-west azimuth hits the coast of France. The two big compass roses in mid-Atlantic are harder to place. They might locate the tropic lines (23-1/2 north and south) or they could represent 22-1/2 latitude (one-fourth of the way from equator to pole). Considering they are a bit closer to 45 degrees than the equator, the tropic lines are the most likely.

Piri Reis’ world map dating from 1513 shows the Atlantic with the adjacent coasts of Europe, Africa and the New World. The second one dating from 1528-29, of which about one sixth has survived, covers the north western part of the Atlantic including the southern tip of Greenland, North America from Labrador and Newfoundland in the north to Florida, Cuba and parts of Central America; and in the south it shows the region from Venezuela to Newfoundland.

Controversy – the Hapgood Hypotheses and Space Aliens

The Piri Reis map has also been the center of controversy. This map was analyzed by Charles H. Hapgood, a historian and geographer at the University of New Hampshire, and his graduate students. They identified what they believe to be a representation of the continent of Antarctic on the map. They also identified the Andes mountain range and an animal that they identified as a llama. Given that Antarctica was not discovered until 1820 and the first European to sight the Andes mountains was Magellan in 1519, they claim that the map contains information not available to Piri Reis in 1513. Their analysis lead to Hapgood’s book Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings (1966) in which he suggests that a lost civilization with high seafaring and mapping skills had surveyed the entire earth in the long ancient past.

There are several problems with Hapgood’s hypotheses. What he has identified as Antarctica on the map might also be a portion of South America. The map does not show Drake’s Passage or the Pacific Ocean. What Hapgood identifies as the Andes mountains are not located along a coast line. Also the animal represented to be a llama on the map, has horns, a characteristic that llamas lack.

Two years after Hapwood’s book was published, his hypotheses received unexpected notoriety when it was incorporated in the controversial best-seller Chariots of the Gods by Erich von Daniken. Von Daniken claimed that information on the Piri Reis map could not possibly have been known by 16th-century cartographers and went on to claim that space aliens visiting the earth provided the data. Not surprisingly most of Von Daniken claims do not hold up to scrutiny.

Notwithstanding being largely forgotten before 1929, Piri Reis has entered popular culture. He is now a character in several video games, including Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed: Revelations. His map also appears in the Colin Wilson’s, The Space Vampires.

I remember reading about this sometime in the past, but don’t remember what I thought about it?