The seven-masted iron schooner Thomas W. Lawson, delivered in 1902, is remembered as the largest schooner ever built and the largest pure sailing vessel, in terms of tonnage, to ever sail. Mostly, however, she is remembered for her rig. She was the only seven-masted schooner in commercial service. She carried primarily coal and oil in her short career. She was lost off the island of Annet, in the Isles of Scilly, in a storm on December 14, 1907, killing all but two of her crew of eighteen and a harbor pilot. Her cargo of 58,000 barrels of light paraffin oil caused one of the first large marine oil spills.

The seven-masted iron schooner Thomas W. Lawson, delivered in 1902, is remembered as the largest schooner ever built and the largest pure sailing vessel, in terms of tonnage, to ever sail. Mostly, however, she is remembered for her rig. She was the only seven-masted schooner in commercial service. She carried primarily coal and oil in her short career. She was lost off the island of Annet, in the Isles of Scilly, in a storm on December 14, 1907, killing all but two of her crew of eighteen and a harbor pilot. Her cargo of 58,000 barrels of light paraffin oil caused one of the first large marine oil spills.

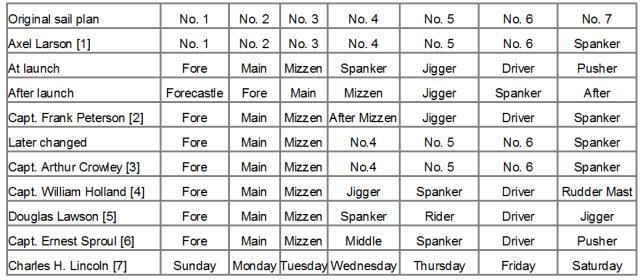

Each of the masts, as well as each of the 27 sails, had to have names. But how does one name seven masts? Looking into it, I found that according to Lars Bruzelius’ The Maritime History Virtual Archives, at least, eleven different naming schemes were used to keep track of the masts. That is right, eleven different sets of names for the seven masts.

The Masts of the Thomas W. Lawson

- Axel Larson, Foreman Rigger at the Atlantic Works of the Boston Plant. Notes at the Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.

- According to Capt. Frank H. Peterson, secretary of the Boston Marine Society Capt. Arthur Crowley told him what the masts were originally called.

- Capt. Arthur L. Crowley, the first master of the Thomas W. Lawson, in a letter preserved at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA.

- Capt. William Holland of Bradford: “Having served as quartermaster on the Thomas W. Lawson, I feel I must know the names of the sticks she had in her.”

- Douglas Lawson was the son of Thomas W. Lawson.

- Capt. Ernest D. Sproul of the Old State House Marine Museum.

- Charles H. Lincoln of the Boston Post and a literary associate of Thomas W. Lawson has said that Lawson told him that the masts were named for the days of the week.

Each of the naming schemes could work. There is a certain utilitarian appeal to simple numbered masts, 1-7. And the days of the week have an undeniable charm. Two of the naming schemes seem more problematic. Two have both a Foremast and a No. 4 mast, which seems like a very bad idea.

I once read somewhere: fore, main, mizzen, jigger, driver, pusher, spanker.

Similar to the scheme at launch, but with a couple rearranged. Yours would be a twelfth version.

It’s worth remembering that the “pure sailing” vessels that we revere — the clipper ships, the super-sized schooners and barques — were in actual fact steam-dependent. A crew of 18 could not have handled the Thomas W Larsen without steam winches. The great clippers such as Thermopylae and Flying Cloud could not dock in most ports without steam tug assistance. There is no hard line “before” and “after” between steam and sail.

Very interesting. Seymour although you are correct, if steam wasn’t available to propel the vessel it was purely a sailing ship! Don’t ruin Flying Cloud’s image!

Capt. Charles H. Lincoln seems to be a landlubber.

The Great Eastern had six masts, labeled (from bow to stern), Monday through Saturday. If a passenger asked a member of the crew where Sunday was, the inevitable response was “Aboard ship, there is no Sunday.”

27 sails? I thought she had 25.