One recurring comment related to the collision between the USS Fitzgerald and the container ship ACX Crystal was that the container ship might not have been able to see the destroyer over the containers stacked on deck. There are photographs of containers on ACX Crystal stacked five high on deck forward of the house. Exactly how far forward did the ship’s blind spot extend? Was the view of of the USS Fitzgerald obscured by the containers stowed on the 2,858 TEU container ship? Are standards for container ship visibility too lax?

One recurring comment related to the collision between the USS Fitzgerald and the container ship ACX Crystal was that the container ship might not have been able to see the destroyer over the containers stacked on deck. There are photographs of containers on ACX Crystal stacked five high on deck forward of the house. Exactly how far forward did the ship’s blind spot extend? Was the view of of the USS Fitzgerald obscured by the containers stowed on the 2,858 TEU container ship? Are standards for container ship visibility too lax?

No doubt the answers to these questions will be answered in the multiple ongoing investigations. The answers will depend on the specifics of the container stow plan on the ACX Crystal as well as the ship’s draft and trim.

Visibility, however, may only be part of the story. Maneuverability — the ability to stop and/or turn the ship — can be even more important.

If we do not know exactly what the visibility was on the ACX Crystal prior to the collision, we do know what it should have been. The SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea Convention) Regulation 22 defines the minimum visibility allowed.

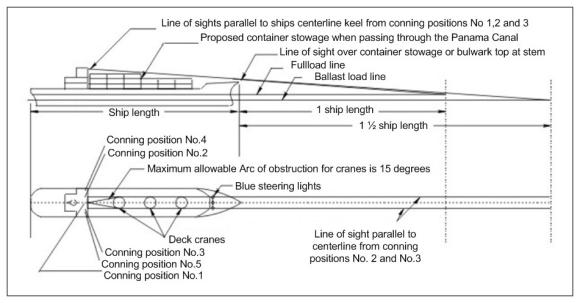

Specifically, “the view of the sea surface from the conning position shall not be obscured by more than two ship lengths, or 500 m, whichever is the less, forward of the bow to 10 deg; on either side under all conditions of draught, trim and deck cargo…” The visibility requirement in the Panama Canal is slightly tougher at 1.5 ship lengths.

In the case of the ACX Crystal, the SOLAS allowable blind spot is about 445 meters (1,461′) or just under a quarter nautical mile.

Panama Canal Visibility Standards

But, if the rules for visibility are two ship lengths, the realities of ship mass ad velocity make job of turning or stopping the ship even more challenging. At design speed, container ships are usually more constrained their ability to maneuver than by visibility.

For example, the international standard for container ships making a crash stop from design speed is 15 ship lengths, or over 7 times the allowable blind spot.

Ships generally can avoid a collision more effectively by turning rather than stopping. The minimum allowed turning radius is 5 ship lengths. The advance, the forward distance traveled in making the turn, is 4.5 ship lengths, still more than twice the allowed blind spot.

What all this means is that if the master on the bridge of a container ship waits to respond to a potential collision until the other vessel is close to his blindspot, there may not be enough time to maneuver the ship to avoid a collision.

Maneuverability is a function of a ship’s speed and the rules are all based on designed speeds. At lower speeds, particularity when traveling slowly in a harbor, visibility may a play a much larger role.

So, until the investigators finish their work we will not know the facts of the Fitzgerald/Crystal collision. Nevertheless, all else being equal, it appears that visibility from the bridge of the container ship is not likely to be a primary cause of the collision.

Thanks to Robin Denny for contributing to this post.

Excellent explanation of an interesting & complex problem Rick….even an old Airedale can understand it!

Lots more to navigation of any moving object than many people realize. But Sir Isaac Newton is always ready to take over for you, and frequently not to your advantage…..

If to your starboard red appear, it is your duty to keep clear.

How much visibility was available to the Fitzgerald and how much control and responsibility was retained in darkened rooms?

The Mk I eyeball is all but it must be given authority.

In my opinion the captain of the ACX Crystal has some of the blame for the collision!!!

IE Years ago on Board the USS Los Angeles, a sea land container ship operating out of the Oakland, Calif Container dock, the skipper’s standing orders, well told to all the mates ( was 3rd mate on board back then) If any vessel comes within ‘one mile’, no matter if we are the stand on vessel in the situation, immediately take evasive action to avoid a collision.

Such a situation actually happened going to/ one day out of Subic Bay, Philippines, west bound, we were, when the USN nuclear carrier Enterprise came up over the horizon from the south, heading north.

The carrier’s bearing not changing, I put the Los Angeles on hand steering and being just within a mile, was about to come left to go astern of the carrier when huge fountains of water under the Enterprise’s stern shoot up higher then the flight deck, and she just ‘sipped right along’ in front of us and was gone over the horizon in lest then 5 minutes.

and further perhaps large size container ships in future should all have their wheel houses up on the bow, not half way back as so many do now.

Consider, the collision situation started at an angle to the bow, not head on, as most do. So visibility over the bow is not the critical issue.. collision avoidance starts with visual lookouts and constant attention to radar and AIS. Managing a close quarters situation starts long before visibility over the bow is a limitation to proper response.

I would say that base on 50 years of seagoing experience this is by far the fairest article I have read. It sums up some of the drawbacks of Navy vessels. Merchant Mariners have to learn the collision regulations almost word for word. Thus it is clear the course of action you should take in assessing collisions and avoiding them. The truth will come out in the inquiries and both vessels will bear a proportion of the blame. Neither vessel will be blamed 100% there will have been mistakes made on both bridges by the OOW who are ultimately responsible for safe navigation and avoiding collisions.The Press should read and understand The International Collision Regulations Rule 2 a Rule 5 Rule 7 Rule 8 Rule 15 Rule 17. before they start to apportion blame.

It’s been 40 years since I stood an underway watch but four things come to mind:

1. Was Fitzgerald steaming independently or in formation? It could make a difference.

2. Underway bridge watch team on my DDG (DDG-5, Adams class) consisted of OD, JOD, QM and BM (me) of the watch, helm, lee helm, messenger, three lookouts plus after lookout. CIC was manned by whatever their normal underway watch consisted of.

3. Skipper was in his sea cabin, if there was anything tricky going on he would’ve been on the bridge. Even deep into the mid watch somebody had to be awake and able to see something.

4. If not a people failure then just perhaps it was an equipment failure. On the Adams class DDG there were two steering engine controls located on the after bulkhead by the bridge access door. We would occasionally shift from one to the other, apparently to even out the wear. What would happen if, for whatever reason, somehow, at a critical moment, the steering engine put the rudder hard over into the stops and withstood any attempts to regain control?

Just thinking.

Rule 5; Look-out

Every vessel shall at all times maintain a proper look-out by sight and hearing as well as by all available means appropriate in the prevailing circumstances and conditions so as to make a full appraisal of the situation and of the risk of collision.

As well as by all available means… Nowadays, electronic prevails over maintaining a proper look-out by sight and hearing. Look-out is mostly kept by ECDIS. Radar PPI should then be overlapped on ECDIS to confirm position exactitude by land mark in coastal waters and to detect targets which do not transmit AIS signal. Unfortunately, overlapping the Radar PPI gives a crowdy ECDIS picture. So the Radar PPI is kept separated from ECDIS thus targets not transmitting AIS might not be detected. The only way is to check the Radar regularly and or set Guard Zones. If the vessel is sailing close by fishing grounds or crowdy waters, Guard Zones will set off all the times. Thence, if Radar is not at the conning position and Guard Zones are not set with ARPA Auto Acquisition and Alarms, an observer sitting at the conning position maintaining look-out by ECDIS alone … might not detect in time a Warship proceeding with her AIS shut off.

Does a Warship proceeding with her AIS shut off in peace time is protected from another and hostile warship? I’m not so sure about that…

Besides, I agree that the range of visibility against deck cargo should be observed. However, how do you keep a proper look-out in dense fog?