We recently posted about the Wellerman and the Sea Shanty Boom on TikTok. We noted that of all the recent strangeness, the most pleasant and least expected has been the explosion of sea shanties on TikTok. It all began when Scottish postman and aspiring musician, Nathan Evanss, began posting shanties and sea songs on the video streaming service TikTok.

We recently posted about the Wellerman and the Sea Shanty Boom on TikTok. We noted that of all the recent strangeness, the most pleasant and least expected has been the explosion of sea shanties on TikTok. It all began when Scottish postman and aspiring musician, Nathan Evanss, began posting shanties and sea songs on the video streaming service TikTok.

Since then, there has been a bit of confusion in some quarters about what the song, the Wellerman is about. (This should not be a surprise, as there are often disagreements about sea shanties, including even what constitutes a sea shanty.) Some have taken the lyric, “Soon may the Wellerman come, to bring us sugar and tea and rum,” as a reference to the infamous Atlantic Triangle Trade which involved trading slaves, sugar, and rum.

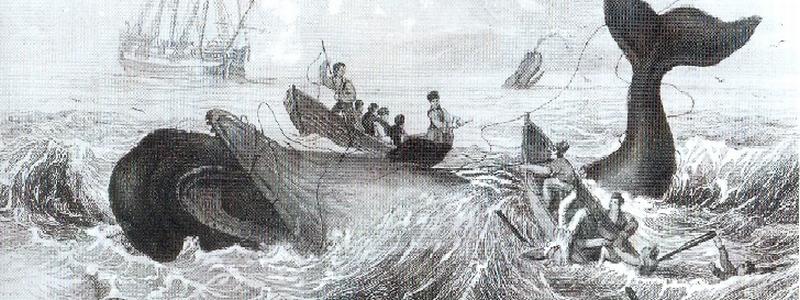

Fortunately, the Wellerman has nothing whatsoever to do with the Atlantic slave trade.It is a New Zealand sea song about whaling, specifically, a whaling company established by the Weller brothers, whose employees and ships were called Wellermen. The Wellerman provides a glimpse into the remarkable cross-cultural whaling history of New Zealand in the early 1800s.

Whereas American whalers sailed from the East Coast of North America to the Northern Pacific to hunt whales and processed the blubber and bone on shipboard, whalers on the South Island of New Zealand hunted whales just off their shores and processed the whales at stations on land.

To establish a whaling station meant making arrangements with the local Māori people. The Sydney-based Weller brothers established their first whaling station at Ōtākou (Otago) on the South Island in 1831. It is not clear what terms, if any, were negotiated, but a few months later, the station and its whalers’ houses were been burned to the ground by a Māori raiding party. Apparently, a subsequent agreement was reached, as the station was rebuilt in 1833 and would grow to become one of the largest whaling stations on the New Zealand coast.

The Weller whaling station and others like it would also benefit the Māori. Kate Stevens, Lecturer in History, at the University of Waikato, writes in the journal Conversations:

Whaling connected Ngāi Tahu [the largest Māori tribe] to the global economy in the early 19th century, providing new and sometimes mana-enhancing opportunities for trade, employment, and travel…

At the same time, Ngāi Tahu communities sought to incorporate whaling men into the rights and responsibilities of whanaungatanga (relations, connectedness). Intimate relationships and marriage were key features of this process, as historian Angela Wanhalla has shown.

Over 140 men had married Māori women in southern New Zealand by 1840, with these couples producing over 500 children. Edward Weller himself married Paparu, daughter of Tahatu and Matua. After her early death, Weller remarried Nikuru, daughter of rangatira (chief) Taiaroa, but left New Zealand without his wife and daughters after the Otākou station’s closure in 1841…

As the whaling industry declined from the 1840s, some whalers (like Edward Weller) proved transient visitors. Many others, like Howell, remained with their families, though most were not as wealthy.

Former whalers turned to fisheries, agriculture and trade. Their mixed communities formed the basis for settlements around the southern region: Bluff, Riverton, Moeraki, Taieri, Waikouaiti.

These early and intense interactions had a lasting legacy in Ngāi Tahu’s whakapapa (genealogy) and collective identity. The sustained contact between Ngāi Tahu and whalers also complicates the myth of whaling as simply a transient and masculine pursuit.

Whaling was indeed a gendered industry; crew were almost exclusively male. But they were also diverse. Native American, Aboriginal Australian and Pacific Islanders all found opportunities aboard ship and in New Zealand alongside Māori and Europeans.

Many of them, we must assume, would have sung or heard shanties like Soon May the Wellerman Come — though none might have expected their descendants in the 21st century to be humming them too.

Thanks to Dick Kooyman for contributing to this post.

You all might like to read this useful addition

Soon May The Wellermen Come. The song is not a sea shanty, (a shanty is a work song and only a work song in which there is a call and response and is used for hauling and heaving) Dates from around the 1860s; refers to the Wellermen and Joseph Weller one of the supply ships owned by the Weller Brothers who ran shore whaling stations on South Island New Zealand in the 1830s and 40s. Its chorus contains lines such as – “And bring us sugar and tea and rum,” – and illustrates the Weller Bros as major suppliers to the shore whaling stations, it relates as what today we would call a company song. The workers at these bay-whaling stations were not paid wages as such; they were paid in kind/slops, clothing, spirits, tobacco and other necessities of life, in the UK this would have been called tommy.

The song was originally collected around 1966 by New Zealand-based music teacher, folk song collector and writer Neil Colquhoun and published in his book “Songs of a young country” Folkestone UK 1972 he had the song from one F. R. Woods. Woods, who was in his 80s at the time, he had heard the song, and another “John Smith A.B”, from his uncle. The latter was printed in a 1904 issue of “The Bulletin”, where it was attributed to one D.H. Rogers. It is possible that Rogers was the uncle of Woods, who worked as a young sailor/shore whaler in the early-mid 19th century and had composed both songs in his later years, eventually passing them on to his nephew as an old man.

The song has been frequently sung in Folk Clubs and by sea shanty singers it is a sea song rather than a shanty and was never in the cannon of the sea shanty which is a deep water work song with call and refrain such as “Blow the man down” or “Serafina”.

Chris Roche:

I have edited corrected, collated and added to what I have found web wise, I am at a loss as to where I have put my copy of Neil Colquhoun`s book “Songs of a young country” published curiously enough on the Bayle at Folkestone, Kent, UK. My home town also from where the Weller family migrated to Sydney Australia. For the record my Daughters married name is Weller a Kentish name of long standing.

The text given is the most complete that I have.

Soon May The Wellermen Come

There once was a ship that put to sea,

And the name of that ship was the Billy o’ Tea.

The winds blew hard, her bow dipped down,

Blow, me bully boys, blow.

CH: Soon may the Wellermen come

To bring us sugar and tea and rum,

One day, when the tonguin’ is done

We’ll take our leave and go.

We had not been two weeks from shore,

When down on us a right whale bore.

The captain called all hands and swore,

He’d take that whale in tow.

Before the boat had hit the water,

The whale’s tail came up and caught her.

All hands to the side, harpooned and fought her,

When she dived down below.

A line we dropped all in pursuit,

She raised her tail, a last salute.

But the harpoon lodged there’s no dispute,

She dived down below.

No line was cut, no whale was freed,

The Captain’s mind was not on greed.

But he belonged to the walerman’s creed,

She took the ship in tow.

For forty days, or even more,

The line went slack, then tight once more.

And boats were lost (there were only four),

But still the whale did go.

As far as I know, the fight’s still on,

The line’s not cut and the whale’s not gone.

The Wellerman makes his regular call,

To the Captain, crew, and all.

Chris Roche http://www.capehorners.org January 2021

Thanks. Very interesting.