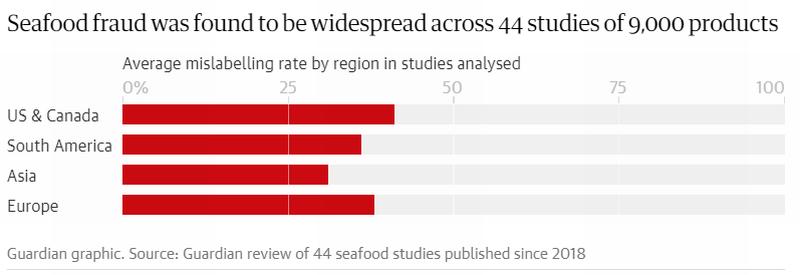

Do you know what you are getting when you buy fish in a store or order it prepared in a restaurant? It isn’t always easy. An analysis of 44 recent studies of more than 9,000 seafood samples from restaurants, fishmongers, and supermarkets in more than 30 countries, performed by Guardian Seascape, found that 36% were mislabelled, exposing seafood fraud on a vast global scale.

The Guardian reports that many of the studies used relatively new DNA analysis techniques. In one comparison of sales of fish labeled “snapper” by fishmongers, supermarkets, and restaurants in Canada, the US, the UK, Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand, researchers found mislabelling in about 40% of fish tested. The UK and Canada had the highest rates of mislabelling in that study, at 55%, followed by the US at 38%.

Fish fraud has long been a known problem worldwide. Because seafood is among the most internationally traded food commodities, often through complex and opaque supply chains, it is highly vulnerable to mislabelling. Much of the global catch is transported from fishing boats to huge transshipment vessels for processing, where mislabelling is relatively easy and profitable to carry out.

Oceana, an international organization focused on oceans, notes that today, more than 90 percent of the seafood consumed in the U.S. is imported, and less than 1 percent is inspected by the government specifically for fraud. With more than 1,700 different species of seafood from all over the world available for sale in the U.S., it is unrealistic to expect the American consumer to be able to independently and accurately determine what they are actually eating.

Despite growing concern about where our food comes from, consumers are frequently served a completely different type of fish than the one they paid for. As Oceana’s nationwide study and others demonstrate seafood may be mislabeled as often as 26 to 87 percent of the time for commonly swapped fish such as grouper, cod, and snapper, disguising fish that are less desirable, cheaper, or more readily available.

The problem is global. One study, representing the first large-scale attempt to examine mislabelling in European restaurants, involved more than 100 scientists who secretly collected seafood samples ordered from 180 restaurants across 23 countries. They sent 283 samples, along with the menu description, date, price, restaurant name and address, to a lab. The DNA in each sample was analyzed to identify the species and then compared with the names on the menu. One out of three restaurants had sold mislabelled seafood.

There is considerable economic incentive to sell low-value fish in place of more popular and expensive species – and even more money to be made “laundering” illegally caught fish, says Rashid Sumaila, a fisheries economist at the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia.

Thanks to Joan Druett for contributing to this post.