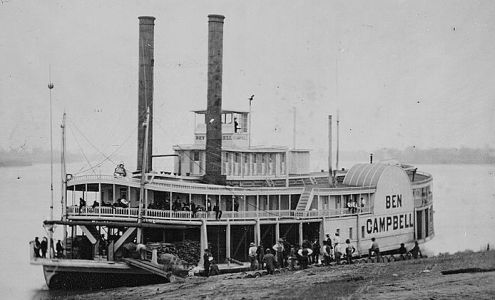

The steamboat Ben Campbell commonly attributed as John Berry Meachum’s Floating Freedom School. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

At a time when programs supporting the American values of diversity, equity, and inclusion are being banned in schools across the nation, it is incumbent on the rest of us to keep alive the history that some are now seeking to suppress. Here is a repost of an account of how far we have come while also being a reminder of how far we still have to go — the story of Missouri’s Floating Freedom School.

The Floating Freedom School was an educational facility for free and enslaved African Americans on a steamboat on the Mississippi River. It was established in 1847 by the Baptist minister John Berry Meachum.

Prior to the Civil War, while Missouri, like many states that allowed slavery, outlawed teaching Black individuals to read, abolitionists like John Berry Meachum found ways around the law to educate Black students.

Meachum was born into slavery in 1789 in Virginia and was moved by his owner several times before eventually settling in Kentucky. Having learned carpentry as a trade, Meachum earned enough money to purchase his freedom. He was also able to purchase the freedom of his wife, Mary, who had been moved to St. Louis by her owner.

In 1825, Meachum teamed up with a white Baptist missionary to establish the First African Church of St. Louis – one of the oldest Black churches west of the Mississippi River. Meachum established a school at the church, where he provided classes to free and enslaved Black students.

In 1847, John Berry Meachum was forced to close the school. Earlier that year, the Missouri legislature had passed a law that made it illegal to provide “the instruction of negroes or mulattoes, in reading or writing”. Meachum and one of his teachers were arrested by the sheriff and threatened.

To circumvent the new state law in Missouri, Reverend Meachum bought a steamboat which he anchored in the middle of the Mississippi River, thus placing it under the authority of the federal government. The new floating “Freedom School” was outfitted with desks, chairs, and a library. Students were ferried back and forth between St. Louis and the Freedom School in small skiffs. The school eventually attracted teachers from the East.

Meachum and his wife, Mary, also helped enslaved people gain their freedom through the Underground Railroad by transporting them across the Mississippi River to the free state of Illinois.

Mary Meachum continued to help the enslaved escape after her husband’s death in 1854. While leading the group across the river on the night of May 21, 1855, Mary Meachum and five of her party were caught and arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The location of their departure from St. Louis is marked by the Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing Site along St. Louis’ Riverfront Trail. In 2001, the site became the first in Missouri to be added to the National Park Service’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom program.

Hundreds of black children were educated at the Freedom School in the 1840s and 1850s. Those who could pay were charged one dollar a month. One of the early students was James Milton Turner, who would go on to establish 30 new schools for African Americans in Missouri after the Civil War.

Learning about the Floating Freedom School

The issue of access to education for black and minority students continues to this day. In April 2025, the Trump regime sent a

“Dear Colleague” letter to school administrators. The letter grossly misstated the law and threaten to cut funding to pre-K through 12 schools, colleges, and universities that invest in steps to level the playing field for students, faculty, and staff. The Office for Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Education (ED OCR) issued an accompanying Frequently Asked Questions document. ED OCR then sent a follow-up letter to PK-12 State Education Agencies on April 3, 2025, directing them to certify their compliance with the agency’s views explained in the Dear Colleague Letter. Because these letters are designed to instill fear and sow confusion, civil rights groups filed suit to have it withdrawn.

The lawsuit was filed last year by the American Civil Liberties Union, the ACLU of New Hampshire and the ACLU of Massachusetts on behalf of the National Education Association (NEA), and the National Education Association–New Hampshire. The Center for Black Educator Development as well as several New Hampshire School Districts later joined the case as plaintiffs.

On February 18, 2026, the U.S. Department of Education conceded the end of its February 14, 2025, “Dear Colleague” directive that sought to restrict diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts in schools and higher education institutions nationwide. Upon the US’s concession that the directive and subsequent certification requirement are vacated – meaning they are formally nullified – the district court issued a final ruling today, permanently invalidating the directive and preventing the government from enforcing, relying on, or reviving it. As a result, the challenged guidance is no longer in effect and cannot be enforced against anyone, anywhere nationwide.

“This ruling affirms what educators and communities have long known: celebrating the full existence of every person and sharing the truth about our history is essential,” said Sharif El-Mekki, CEO at The Center for Black Educator Development. “Today’s decision protects educators’ livelihoods and their responsibility to teach honestly. At a time when many communities are facing severe teacher shortages, this signals that teachers can enter and stay in the profession, bringing their full selves to the classroom and fostering inclusive environments that prepare students for the future.